Nathalie Marins, Ricardo Summa & Daniel Consul

Mar 2025

Currency devaluations can disrupt developing economies by raising import costs and food prices, which in turn reduces real wages. This impact is particularly detrimental to lower-income households, which typically allocate a substantial portion of their income to essential goods. Consequently, when the local currency weakens, governments encounter increased political pressure due to rising prices that erode purchasing power. Throughout 2024, the Brazilian real faced a continuous process of depreciation that intensified in December, prompting headlines accusing recent fiscal policy decisions of triggering a full-blown currency crisis. However, a closer look at the data suggests that external financial factors, monetary and exchange rate policy choices, and a short-term “flight to quality” played a far more significant role in driving this depreciation. In the following pages, we will examine the behavior of Brazil's currency in 2024 and explore the factors behind this trend.

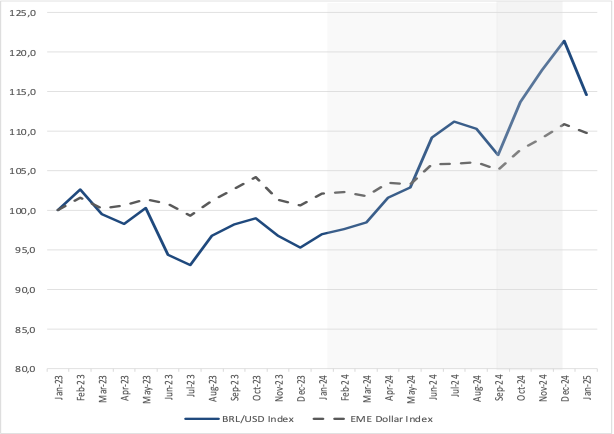

Brazil's currency followed the general depreciation trend of emerging market currencies, amid a year when the US Dollar gained considerable strength over many other currencies. However, in 2024, its devaluation was more pronounced, as shown in Figure 1. By December 2024, the Brazilian Real had depreciated approximately 27% against the Dollar compared to its end-of-period value in December 2023. In contrast, the Emerging Market Economies Dollar Index (EME Index) recorded a depreciation of just 10% during the same period.[1]

Figure 1 – Nominal exchange rates

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

To analyze this trend, we can divide the Brazilian currency's behavior in 2024 into two distinct periods. From January to September, the nominal exchange rate gradually depreciated, with the Real losing about 10% of its value. The subsequent period, in turn, was marked by a sharper devaluation, with the currency devaluing an additional 13% over just three months, with a marked distress in December. Let us see what the explanations of such behavior can be. We first look at the structural pattern of external vulnerability in terms of external liquidity and sustainability indicators over the last three decades. After that, we check the pattern of the balance of payment flows in Brazil in 2024 for the short-run analysis.

Increased external short-term vulnerability?

External vulnerability indicators are typically among the first factors considered when explaining a distressed currency. Throughout the 20th century, many peripheral countries faced periods of balance‐of‐payments constraints and external debt crises, which prompted a series of studies dedicated to developing indicators that could function as warning systems to monitor when a country might be approaching a potential currency crisis.

Since the mid‐2000s, many of these economies—including Brazil—have shown improvements in these external account indicators. Specifically, Brazil has built up a high level of foreign reserves. Also, in 2024, short-run external debt to international reserves in US$ remained below 30%, a quite comfortable level, and international reserves covered nearly 10 months' worth of imports, according to data from IDS World Bank[2]. Another interesting aspect of the Brazilian external accounts was the “de-dollarization” of its liabilities in recent years, as documented in Rosa and Biancarelli (2016, 2024). This means that a higher share of Brazilian external liabilities (such as public bonds and shares held by non-residents) is denominated in its own currency, which transfers the exchange risk to non-residents and reduces the external vulnerability[3].

This stronger external position is reflected in its CDS—a proxy for sovereign spreads—which has fluctuated comfortably below historical averages and has in fact decreased since January 2023 as can be seen in Figure 2. Therefore, the recent depreciation of the Brazilian Real does not appear to stem from external liquidity problems, as indicated by traditional indicators, nor from any structural shift in the country’s risk profile.

Figure 2 - Sovereign spread

Source: JP Morgan

Current account and financial flows in 2024

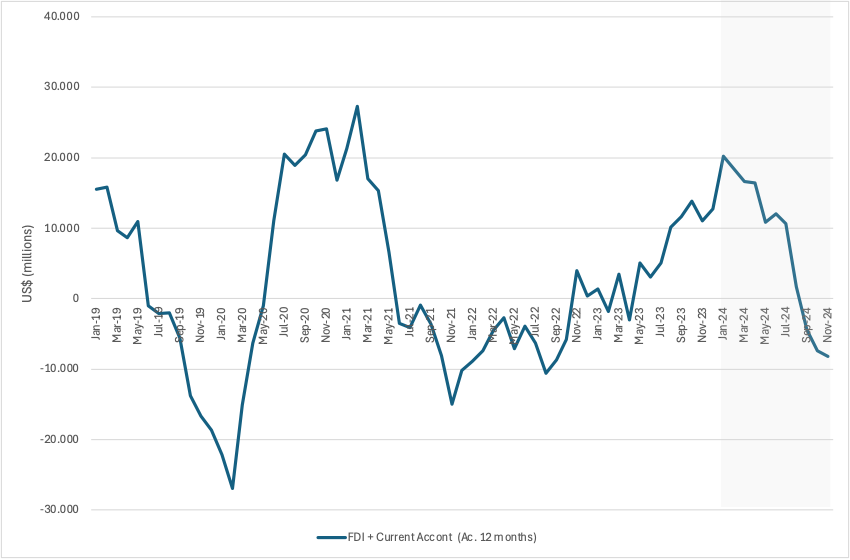

Let us take a closer look at what happened to Brazil’s current account and financial flows in 2024. As mentioned earlier, the country has had current account deficits in recent years. Despite being a net exporter, net outflows of profits, dividends, and interest exceed the trade surplus, creating an overall deficit in the current account. In balance-of-payments accounting, these deficits are offset by capital and financial inflows. Among these flows, foreign direct investment (FDI) is seen as a more stable source of external financing than short-term capital inflows, being less responsive to interest rate differentials[4]. Figure 3 shows the balance between net foreign direct investment and Brazil’s current account, where positive values indicate that the sum of net FDI and current account balances is in surplus. Since net foreign investment remained consistently positive during this period, any negative value implies that the current account deficit exceeded net foreign investment.

Figure 3 – Balance between net foreign investment and current account

Source: Banco Central do Brasil

Data from Figure 3 indicates that this balance weakened steadily over the course of 2024, moving from a surplus of US$20 billion in January to a deficit of US$9.2 billion in December. Although net foreign investment did not change significantly during the year, the current account deficit rose markedly from US$20.9 billion to US$55.9 billion by December, largely due to a sharp increase in imports of goods and services. This import rise was driven by robust economic growth and faster investment expansion in 2024.

A common way to cover such deficits has generally been through portfolio inflows. In 2024, portfolio net flows were still positive, but a little bit lower than the US$9.2 billion deficit between net foreign investment and current account recorded at the end of 2024.

Figure 4 – Portfolio flows and capital account

Source: Banco Central do Brasil

In 2024, however, this relatively small gap between portfolio net flows, net foreign investment, and the current account was amplified by a new and significant source of capital outflows. These arose from rising outflows tied to cryptocurrency and other digital transactions—recorded in the capital account rather than the financial account—which have been growing since 2023. By December 2024, the capital account had accumulated a deficit of US$20 billion. When the portfolio and capital accounts are combined, the total deficit reached US$15.6 billion, putting additional pressure on the nominal exchange rate throughout the year.

While portfolio flows remain closely tied to interest rate differentials, outflows associated with cryptocurrencies and other digital operations, such as online betting, do not. As a result, compensating for the increased deficit in these flows may require higher interest rate differentials.

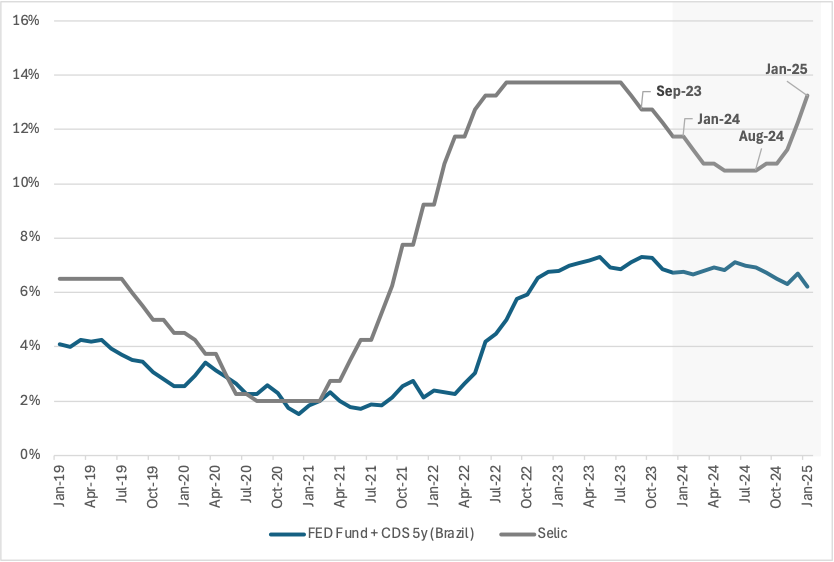

One common way to approximate these differentials is by subtracting the U.S short-term rate (Federal Funds rate), adjusted by the CDS spread, from the domestic policy rate. Hence, both domestic and external policy decisions play a role. As shown in Figure 5, the nominal interest rate differential has remained positive but has fallen below its historical average in recent years.

Figure 5 – Nominal interest rate differential

Source: Banco Central do Brasil, JP Morgan, Federal Reserve

This lower differential can be largely attributable to the Brazilian Central Bank’s decision to reduce the base rate in the second half of 2023, even as the Fed Funds rate stayed relatively high. This policy choice weakened the interest rate differential and—when combined with a higher current account deficit and reduced financial inflows (linked to cryptocurrencies and foreign direct investment)—helps explain the process of nominal exchange rate’s devaluation during this period (IPEA, 2024)[5].

Figure 6 – Nominal interest rates

Source: Banco Central do Brasil, JP Morgan, Federal Reserve

It is also worth noting that in 2020, the Central Bank set the nominal domestic rate below the external rate. This rate-cutting cycle began in late 2019 and kept the base rate at historically low levels throughout 2020. In the turbulent environment of the pandemic, these negative interest rate differentials contributed to portfolio outflows and a sharp process of nominal exchange rate depreciation of more than 35%.

Summing up, the behavior of the current account in 2024—marked by increased imports due to stronger economic growth and investment, along with a structural outflow of cryptocurrencies—likely required a higher interest rate differential (rather than the lower level brought about by the Central Bank’s rate-cutting cycle) to attract portfolio inflows. Taken together, these factors may help explain the nominal exchange rate’s devaluation from January to September 2024.

The distress in October – December

Between the start of October and the end of December, the nominal exchange rate depreciated by an additional 13%, representing a sharper and faster devaluation than in the previous nine months. This turbulent movement created a period of distress in the foreign exchange market to the extent that covered interest parity temporarily broke down (Garcia and Maia, 2024). When deviations from covered interest parity are correctly measured to include transaction costs, they imply potential risk-free profits—a situation that typically occurs only under severe financial stress and sort short-run liquidity shortages of hard currency (Cieplinski et al., 2018).

December also tends to bring higher demand for dollars, as firms typically remit profits and dividends abroad during that month. Figure 7 illustrates this seasonality in Brazil’s dollar transactions, highlighting greater volatility in December. Given this pattern, some degree of devaluation is to be expected toward the end of the year.

Figure 7 – Average volatility of the Seasonality in exchange rate contracts (commercial and financial balance)[6]

Source: Banco Central do Brasil

However, in addition to this seasonal factor, a “flight to the dollar” occurred, driven by uncertainties surrounding the U.S. elections and their possible repercussions (Martins, 2025). During periods of global turmoil—even those originating in the United States—investors often flight to the dollar as a safe haven (Serrano, 2008). This movement affected not only emerging-market currencies but also those of advanced economies (the DXY index fell by 8% in the same period) [7]. In Brazil’s case, the outflows were primarily from residents transferring funds abroad, facilitated by recent deregulations in the foreign exchange market and the rise of fintech platforms that allow both firms and households to hold dollar deposits (Martins et al., 2023).

Finally, it is worth noting that, throughout most of this period of distress, the Brazilian Central Bank took minimal action in the foreign exchange market (Lins and Mantoan, 2024). Data on spot, repo, and derivatives interventions reveal that between 2021 and November 2024, the Central Bank conducted very few operations, and those were relatively small in magnitude, as can be seen in Figure 8.

Figure 8 – Interventions in foreign exchange rate markets

Source: Banco Central do Brasil

Return to normality and the role of policy

By mid-February, the nominal exchange rate stood only about 3% more depreciated than it was at the end of September, suggesting that the sharp depreciation in late 2024 was partly and quickly reversed.

Several events contributed to this development. In December, the Brazilian Central Bank intervened significantly by selling dollars spot and through repurchase agreements in the spot market, marking its largest monthly intervention since 2000 (Figure 8). In addition, the Central Bank substantially raised the base interest rate and issued forward guidance for two more hikes of 1 percentage point each in early 2025.

While these actions seem to have solved the surge in dollar demand, the higher interest rate differential also helped attract portfolio inflows, offsetting some of the deficits discussed earlier in this article. The result of these measures, the lower seasonal demand for dollars, and a partial reversal of the recent flight to the dollar suggest that the worst pressures may have been over.

Notably, this stabilization occurred without any major change in Brazil’s fiscal conditions and main indicators, such as the primary deficit-to-GDP ratio or domestic public debt-to-GDP ratio). This reinforces the view that exchange rate dynamics depend far more on external factors (like overall international liquidity conditions and the U.S. dollar flows between residents and non-residents) than on the government's spending, taxation, and indebtedness in domestic currency. In fact, the Brazilian treasury’s successful bond auction on February 18, 2025, in which demand far exceeded the US$2.5 billion in 10-year sovereign bonds offered, suggests that international investors are not so concerned about Brazil’s domestic fiscal situation. Additionally, outflows at the end of 2024 were primarily due to residents transferring funds abroad.

Moreover, the effectiveness of the Central Bank’s spot interventions suggests that the emphasis on the derivatives market for exchange rate determination may have been overstated, at least in this recent episode. In derivatives markets, the demand for foreign currency does not necessarily involve acquiring actual currency but rather reflects speculation on exchange rate movements (the change in exchange rate) to seek profit or hedge against risks of exchange rate change. Thus, while some speculative or hedging operations can indeed be addressed through swaps in the foreign exchange market, the fact that spot interventions not only halted but partially reversed the depreciation underscores the critical role of the spot market in this episode.

What lessons can we draw from this episode? First, we think this indicates that the Brazilian Central Bank should keep a close eye on and mind the size of the interest rate differential, taking into account the state of the external current account and financial flows when setting the base rate. Second, it points out that timely interventions can indeed help during periods of exchange rate distress. Therefore, given the inflationary and distributional consequences of sharp depreciations, it may be prudent for the Brazilian Central Bank to fear “too much floating” and use its available tools promptly to prevent excessive pressure on the domestic currency and intervene to stabilize it when necessary.

References

CIEPLINSKI, A.; BRAGA, J.; SUMMA, R. Avaliação empírica do teorema da paridade coberta de juros entre o real brasileiro e o dólar americano (2008-2013). Nova Economia, v. 28, p. 213-243, 2018.

CORRÊA, V. P., MESSEMBERG, R. P., BRAGA, J. M., & SILVA, R. P. (2012). Instability of capital inflows and financial assets returns in the Brazilian Economy. V Encontro Internacional da AKB, 1-35.

GARCIA, M.; MAIA, P. Para que servem as intervenções do BC? Valor Econômico, dez 2024.

LINS, B.; MANTOAN, E. Dólar Alto no Governo Lula: Razões e Impactos de uma Política Cambial Passiva. Le Monde Diplomatique Brasil, 9 de dezembro de 2024

IPEA Carta de Conjuntura : n. 65, out./dez. 2024 Box 3 – Fatores que tem influenciado a taxa de câmbio. Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (Ipea). Dez-2024

MARTINS, G. Trump, Volatilidade Cambial e Vulnerabilidade Externa: Impactos para o Brasil. Blog, MADE-USP, In: https://madeusp.com.br/2025/02/trump-volatilidade-cambial-e-vulnerabilidade-externa/

MARTINS, N., SARNO, P. M., MACAHYBA, L., & FILHO, D. B. (2023). Fintech Companies in Brazil: Assessing Their Effects on Competition in the Brazilian Financial System from 2018 to 2020. In The Fintech Disruption: How Financial Innovation Is Transforming the Banking Industry (pp. 349-372). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

MEDEIROS, C.; SERRANO, F. Capital flows to emerging markets under the flexible dollar standard: a critical view based on the Brazilian experience. Monetary Integration and Dollarization, p. 218-42, 2006.

PEREIRA, V.; CORRÊA, V. Vulnerabilidade externa de países periféricos e o perfil da componente financeira do Balanço de Pagamento–uma análise para o caso brasileiro entre 2000 e 2014. ANPEC- [Brazilian Association of Graduate Programs in Economics], 2016.

ROSA, R.; BIANCARELLI, A. Passivo Externo, Denominação Monetária e as Mudanças Na Vulnerabilidade Externa Da Economia Brasileira . Anpec 2016.

ROSA, R.; BIANCARELLI, A. ORIGINAL SIN E A MOBILIDADE DOS FLUXOS DE CAPITAIS PARA A ECONOMIA BRASILEIRA (2002–2023). Anpec 2024.

SERRANO, F. A economia americana, o padrão dólar flexível e a expansão mundial nos anos 2000. O mito do colapso do poder americano, p. 71-173, 2008.

SERRANO, F.; SUMMA, R.; AIDAR, G. Exogenous interest rate and exchange rate dynamics under elastic expectations. Investigación económica, v. 80, n. 318, p. 3-31, 2021.

The authors would like to thank Julia Braga and Franklin Serrano for many useful discussions and valuable comments on previous versions of this article. The usual disclaimers apply.

[1] Although this index places significant weight on the Chinese currency—as it is composed of the US's main EME trading partners — the devaluation of the Brazilian currency was steeper than that of its Latin American counterparts. For example, the Mexican peso depreciated by approximately 23% during this period, while the Chilean peso and Colombian peso experienced devaluations of around 12% and 15%, respectively.

[2] For a discussion about indicators of external liquidity and solvency, see Medeiros and Serrano (2006).

[3] In fact, exchange rate depreciation reduces the stock of external liabilities denominated in domestic currency, when converted to US$.

[4] Note that when the inflow involves a controlling claim of a company’s stocks - defined as a stake of at least 10% of the company – the investment is registered as a foreign direct investment flow. Given this fine distinction between these flows and the portfolio flows, part of FDI presents a similar behavior to short-term flows. This is the case, for example, in Brazil, as documented by Correa et al., 2012 and Pereira and Correa, 2016. Nevertheless, part of foreign investment is driven by longer-term growth expectations and the specific integration into the global value chains of each country.

[5] For a theoretical discussion on exchange rate dynamics integrating interest rate differentials and other financial and trade flows, see Serrano et al. (2021).

[6] The average volatility was calculated based on the monthly variance of daily exchange rate contract data (commercial and financial balance) from September 2008 to December 2024.

[7] This means that the US$ Dollar appreciated in relation to other important currencies. The U.S. Dollar Index ( DXY) is an index (or measure) of the value of the United States dollar relative to a basket of foreign currencies of advanced economies: Euro, Japanese yen, Pound sterling, Canadian dollar, Swedish krona and Swiss franc.